A round table of invited experts discussed the idea of establishing a vision statement for a proposed university in northern Canada. Canada is unique in circumpolar countries for not having a university in the north. As a result all of the university level training is done in the southern parts of Canada or as joint, usually temporary, ventures in the north with colleges or as special projects. The discussion framed many of the important issues including the natural, social, political, and environmental aspects that necessarily underpin the development of a major institution such as a university in northern Canada.

The fundamental messages were that the North needs an institution of higher learning that is safe for its students and that incorporate the aboriginal cultures, languages, and expectations.

Joanne Barnaby

The first speaker was Joanne Barnaby, a well known expert and advocate for traditional knowledge and the establishment of the Dene Cultural Institute in Hay River, NWT. Joanne was born in northern Alberta, raised in Ft. Smith, and attended the Ft. Providence mission school and Pine Point where she experienced racism for the first time.

Key concepts:

1. Cultures, values and ways in the north are a source of strength and source of answers to modern challenges

2. Aboriginal people in particular have something distinct to offer the world – our way of relating to creation, to each other as humans and to life on earth and the universe

3. Issued a call for us as Aboriginal people to approach the old/ancient knowledge to both ensure its integrity through research that honours spiritual nature of the knowledge, and also to ensure that it can also be communicated by other cultures

In 1969 when Joanne was still only 10 years old there was a meeting of the chiefs, and somehow the other communities who didn’t know Pine Point assumed it was a Dene community. Joanne was chosen to go to the meeting as an aboriginal person. This early experience presaged her later life: at a young age she was aware that she was different. She went from that awareness to challenging her teachers in High school, where was met with a challenge back by one of the teachers. The teacher agreed she was right, that there is nothing in this education that teaches about the north and challenged Joanne to do something about it. This challenge resulted in the development of a history project, which in turn resulted in a publication; a big thing in those days. This enabled Joanne to travel to may different locations in the North and to interview the Elders. Her love and understanding of her own culture and knowledge systems grew. Over the years she did many things to work with Traditional Knowledge.

In Joanne’s opinion, valuing one’s own culture and knowledge systems is not only needed, but should be desired by others in Canada and elsewhere. Cultures, values and ways in the north are a source of strength and source of answers to modern challenges; Joanne stated that we are missing out on an opportunity to share those insights effectively with the rest of the world because there is no institution or system in the North to make that possible. In her words, if we ignore those opportunities, we hurt ourselves and deprive ourselves of ways to ensure our long-term survival as human beings and other life on this planet.

Joanne emphasized that aboriginal people in particular have something distinct to offer the world – our way of relating to creation, to each other as humans and to life on earth and the universe. She noted carefully that the aboriginal way of perceiving and relating to the natural, cultural, and spiritual world is poorly understood by western science and by modern knowledge-generation systems. She expressed her concern that all of us, even aboriginal people have changed our relationship with the natural environment – we are missing opportunities to build personal relationship in the universe that is rich with insights. Joanne essentially issued a call for us as Aboriginal people to approach the old/ancient knowledge to both ensure its integrity through research that honours spiritual nature of the knowledge, and also to ensure that it can also be communicated by other cultures. Most importantly it is important for western institutions and people to understand that our traditional knowledge system is living; it continues to develop and evolve. It is not static and it is not something that is only relevant to the past.

Joanne concluded that she has a dream of designing a curriculum and programs in my old age that helps to describe ways of drawing out what is in our genes.

Gavin Gardner

Key Concepts:

1. Nineteen of 22 modern treaties are located north of 60, so this is a tremendous opportunity for examining the potential for self-governing

2. In the face of climate change and its impacts, how will we as northerners maintain our way of life and way of looking at the world?

3. The social safety net is failing Aboriginal Canadians – it is a flawed system because there is no single institution that provides for outreach and social programming in a way that communities can identify with

4. Current assessment tools and institutions don’t take into account collective identity and traditional teachings of aboriginal people

Gavin Gardner was asked to step in to take the place of Chief Mark Wedge whose step sister had just passed away. Gavin acknowledged that it was a big task to take Mark’s place. However, he was quick to point out that he too has a great interest in the subject of education in the North.

He said he would try to pass on what he knows is Mark’s thinking, but also to put some of that in his own words and ways of understanding what is needed.

Gavin began by saying that Ta Sha de Hene (Mark) Wedge is very passionate about a culturally-relevant, made-in-the-north university. These words would come to be a constant connection for everyone in the next three days. He tackled three different themes: politics, social opportunity, and the incorporation of culture into the academic program.

Political opportunities for academic institutions in the north have to contend with the realities of aboriginal history. In some cases this provides a major opportunity. Nineteen 22 modern treaties are located north of 60, so this is a tremendous opportunity for examining the potential for self-governing. The impact that self-government has on training requirements in the north has not really been addressed because only a few opportunities have been available so far. Gavin suggested that his guiding question in this was: what might it look like in the north in 20 years when you see the effects of self-government? He commented that it was certain there will be totally different ways of doing things in areas such as social work. Given this reality, Gavin argued for a different way of training. Although he didn’t attempt to answer his own question, he did ask the audience, what impact devolution might have on training requirements? Gavin also made it clear that climate change was real and not to be ignored politically. Of the many impacts, he wondered how the North should prepare for the influx of people from the south to the north. He especially was concerned about how we as northerners maintain our way of life and way of looking at the world?

In his second theme, social opportunity, he began by emphasizing that the social safety net is failing Aboriginal Canadians – it is a flawed system. Gavin noted the gaps in academic achievement, high incarceration rates, and many other indices of problems. He held out hope by arguing that we need to approach outreach and social programming in fundamentally different way. He described how currently we are forced to take pieces of training here and there, because there is no single institution that provide for outreach and social programming in a way that communities would identify with.

Gavin used the example of Carcross. This organization is trying to base policy and programs on culture, including the medicine wheel. They are forced to shoe-horn this training in right now because no institution addresses the full range of needs. He noted the hopeful signs that the Northern institute of social justice, which is brand new, will perhaps help, but he felt it too new to say for sure.

Gavin used his educational background to remind everyone that it takes time for an individual to move from pre-contemplation to taking action. Indeed he suggested there are five separate stages in this process. To leave one out is likely to result in the individual stopping before he takes action.

In elaborating on social opportunities, he remarked that it is fundamentally important that if we are to build aboriginal self-government it must be based on Traditional Knowledge. Culturally-relevant assessment tools are needed because the current assessment tools don’t take into account collective identity and traditional teachings of aboriginal people.

Gavin’s third theme argued that a university in northern Canada would (or could) provide an incredible opportunity to incorporate culture into the structure of an academic program. Classrooms he said, don’t have to have four walls, they can be in places that are important to people of the north such as out on the land. If a university in the North is to be accepted in the north by aboriginal people it must pay attention to these aspects. To illustrate this point Gavin said that one of the other great opportunities that he had was as a global fellow of the Gordon Foundation through which he did international research on how other communities have made self-government a reality. He looked at case studies, including Norway (Sami Parliament) – Kautokeno which is focused on journalism and early childhood education. The Sami University College has taken two areas: journalism and education, both are taught in the Sami language and through a cultural lens. Education of children and journalism speaks to the need to incorporate language and this speaks also to what is important here for the north: storytelling and children.

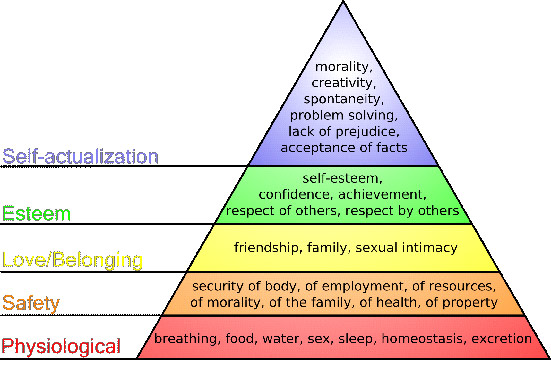

Referring to motivational theory, Gavin said emphatically that Maslow’s hierarchy of needs is wrong (see Appendix #2). Gavin argued that instead, culture is at base, and needs are appropriately thought of in a circle. Gavin argued that it is more a whole integrated circle of needs. Thus, he argued, we have to look at a concept with culture at the base to build institutions. This is a fundamentally different way to look at human development. A unique way we have to look at academic institution building.

Kyla Kakfwi

Key Concepts:

1. Why should we have to choose going south over what we have at home?

2. What we have in the North is equally important learning and teaching to what is available in the south

3. Dechinta wants to create a stage for dialogue, discussion, and a safe and welcome place for higher learning

4. Any new northern university will need to be safe and welcoming to students

5. It is possible to begin at the grass roots level and to do it yourself.

Kyla is the program manager of Dechinta, a highly innovative program of teaching traditional knowledge on the land in cooperation with university programs in the south. Dechinta originated here in the Northwest Territories in late 2009. Erin Freeland-Ballantyne, who is a PhD candidate at Oxford, but grew up in the north, originally founded Dechinta. Erin’s father owns a lodge outside of Yellowknife, so since childhood she spent a lot of time on the land. She, like all of us, Kyla noted, had to go south for university. One day, Kyla said, I had a conversation with Erin about my brother, who is very smart but cannot make it through school system because he would rather be in the bush and learn from his grandfather. Erin couldn’t stop thinking about this: what if this was the university? Would people from the North come to teach if we found a way to have this teaching recognized as valuable on the level of a university? What if we had a university right here at Blatchford Lake?

Kyla described how Erin came up with a concept and forwarded the idea to a lot of people. Soon they had an enthusiastic advisory group and Erin lined up support from local institutions, such as the Institute for Circumpolar Health Research and the University of Alberta. Together they began a visioning session with northern students who had gone to southern university (successfully or not) to talk what a vision could look like. An advisory team was struck. Kyla came on board shortly after that.

Kyla was careful to acknowledge that we live in a modern world. She noted that there is a lot to learn in a southern university, but at the same time, she asked: “Should we have to choose going south over what we have at home?”

Kyla posited that what we have in the North is equally important learning and teaching to what is available in the south. She emphasized the importance of finding a way to ensure that that the value of northern teachings is recognized internationally. Kyla described the progress to date: they had a pilot semester this year in June: three courses, just to see: does it work. They were particularly worried if the students would be willing to spend three weeks in the bush. The answer was a resounding yes, in fact the students would be happy to spend longer than three weeks in the bush – they all wanted to be there longer. There were two instructors for every course, at least one of them a northern expert and also guest speakers. The program tried to address issues that prevent northern people from getting an education. In the future, when Dechinta has full semesters, it will be five weeks on the land. Dechinta is family inclusive: in this semester they had six students and seven children. Because it was in the summer they had only child care, but when they have full semesters Dechinta plans to have teachers there to give children the regular curriculum.

For the 3-week pilot this past summer Dechinta had full scholarships for each of the 6 students. The goal is always to have an affordable program. It’s important to have the option for northern students, but it is not only valuable for northern students. For the pilot we had only northern students, but in the future the courses will be open for others, including from the south or from outside of Canada. Dechinta wants to create a stage for dialogue, discussion, and a safe and welcome place to learn.

Everyone wanted to stay longer; the program had one academic professor and one northern expert full time. There was a range of speakers. The program is family inclusive to encourage young children (7 children attended) – thus child-care is critical. Full scholarship was available for pilot but in the long term, the goal is enabling affordable access even if full scholarship is not a requirement.

The Dechinta lessons demonstrate that any new northern university will need to be safe and welcoming to students.

Anne Crawford

Key Concepts:

1. Fundamental sources of power imbalance were and are at the heart of this issue

2. Barriers that were constructed to participation were imposed by geography, lack of access, or language

3. Eventually when Nunavut was created we had a climate where professional legal training was possible.

4. Because credentialism is a topic with some ministers who want an Akitsiraq-style program for accounting and other professions as well as the legal profession this dialogue is getting more active

Anne comes from a legal background and a career as Conflict of Interest Commissioner in the NWT. She is also Dean of the Akitsiraq program that is designed to produce law degrees acceptable to university standards, but classes are held in the North.

Anne began by placing the Akitsiraq experience in perspective then discussed the issues of credentials and finally of potential institutions in the North.

Fundamental sources of power imbalance were and are at the heart of this issue, she began. Akitsiraq was born out of the court room. A court room is a public forum, lawyers do that part of their work in public. Lawyers are thus very visible in communities. Many lawyers have been in the North for a long time and recognized the inadequacy of what is possible for us to do. The kinds of barriers that were constructed to participation were imposed by geography, lack of access, or language. They saw the inherent value, potential and intelligence of people who didn’t have access to those credentials. Historically, lawyers were not trained at universities they were trained by working in a law office. More recently lawyers evolved into standardized training and examining. Would it be possible to do this training again? Possibly, but populations in the North were not large enough to bring enough people into the profession. The lawyering community was not large enough to have a viable apprenticeship and professional training regime without additional supports in place. A law school was the only solution.

But people initially weren’t very receptive to the idea. Some smaller project were started, and then the effort switched to campaigning in the lead-up to the creation of Nunavut on the opportunity to train lawyers. Anne and others focused on a particular piece of education the legal profession. She described receiving the news of the results of the campaign as follows:

“We were so happy at the news that we had been funded. On the phone they said: yes you have been funded to train prison guards and..? I almost hung up the phone.”

Eventually when Nunavut was created we had a climate where professional legal training was possible.

The initiative was finally enabled when Nunavut became separate from the NWT. In 2001 the first intake of students went forward. It was a four-year program, one-year longer than is normally the case. This was necessary because many of the students were unfamiliar with text-book style of learning and teaching, and law is very textbook-oriented. The people who came had life experience bringing more than one understanding of the world. At first everyone was cautious, but there were fewer drop-outs than expected. This demonstrates real success. The program brought people not only into the legal profession, but also into being involved in civic society, in dialogue, in sharing power. The program had 11 graduates with a BA of law, 9 of whom have passed the bar exam. They are now working in all kinds of fields, as family lawyers, as prosecutors, in Aboriginal Organizations, in advocacy, in the police force [one is now Mayor of Iqaluit].

So it was a demonstrable success. And there was a great hope to do it again, but with changes in government, so there have been changes in priorities and so far not sufficient interest in developing a second cohort. It hasn’t been as simple as just showing how successful it is and then expecting funding for a second time. The people involved in the program want to contribute to a public dialogue on the idea of civic society. Anne described how difficult it has been to keep the idea going, to maintain the discussion on power differences and law on the ground. She continues to advocate for a second cohort. The idea is to collaborate with the University of Ottawa to deliver part of their program in Iqaluit with the idea to continue having this education in the North. The University of Ottawa will deliver some of their legal programs in Iqaluit in 2012.

The program had some local experts and attracted some of the best law professors from all over Canada to teach those courses. The success of the students validated what was accomplished.

Anne then returned to the broader topic of the discussion and the question of what do we need in the North? Lawyers, social workers, miners? We have people working in these professions in the north but in para-professional settings, she noted. Now, there is more active dialogue with other initiatives for post-secondary education in other fields, for example for accounting.

Anne told us an anecdote to introduce the idea of credentials in which she imagined a picture of a minister walking into one of these international wildlife arenas with people who lived and worked there for a long time, and if they then went to get the credentials they could blow the doors off the system with their experience and perception. These could all be careers if kids were able to get these credentials. There is some legitimacy around the question of validating knowledge, but there is a power inequality that needs to be challenged. She said there had been 6 public dialogues this year – some with private funding to do it – all to maintain discussions around power, law, etc. She was hopeful that because credentialism is a topic with some ministers who want an Akitsiraq-style program for accounting and other professions that this dialogue is getting more active

She concluded by suggesting that it is necessary to use people with high office to gain credibility (Justice Bev Brown was crucial in her support). She emphasized that there are many money- and revenue- producing practical jobs that could benefit from this model. In the North there is no need or even any real way to disconnect the strong cultural base from practical skills/employment benefit. The difficulty right now is the need for strong credentialism supported by the government. Anne’s call to action was: “Right now we have a capturing of power!”

Aaju Peter

Key Concepts:

1. Talking of a university coming from the wisdom of the past for our future generations

2. The reason the law school was successful was because they had an Elder who insisted on teaching the students traditional laws and language

3. How can we make the Elders be seen as professors?

4. Trying to have BOTH Indigenous and western knowledge and systems, and to do it wisely

Aaju is a graduate of the Akitsiraq program but is best known as a high fashion designer of clothes especially using sealskin. Aaju provided special insights because of her ability to capture our imagination using songs that she knew from her past or that she had composed.

Aaju began by thanking everyone and recognizing the people of the NWT. She defined herself as from Nunavut, which means ‘off a territory’ because the people are dependent on that territory for their existence.

She sang a song: “… from my ancestors. Where they are from most of it is ice and the hunters had to be aware of the conditions. The songs is about a man who is going out on the land looking for game, looking for seals because back where his family is, there is no fat. If there is no fat, you cannot live, you can’t heat, there is no water. The only sign of game that this man sees are his own footsteps. This is why we are here, talking of a university coming from the wisdom that is passed on for our future generations.”

Aaju was adamant that the reason the law school was successful was because they had an Elder who insisted on teaching the students traditional laws and language. Aaju said without that teaching they couldn’t have succeeded: the concept of ownership for example – in an area where you belong to the land and not the other way around; and when you are working in law the concept of finding somebody guilty is impossible if you do not have this concept in your own language. She gave further examples such as: “How do we explain concepts like “fee simple”, “property”, “guilty” and “sovereignty”? In Aaju’s traditions, the welcome gesture in a territory is an expression of ‘sovereignty’, which is rooted in sharing and respect, not in ownership.

Aaju made everyone aware of just how different the concepts are in the western legal system from those of her own culture. This became a metaphor for all the other potential aspects of developing a university in the North. As the students were studying law and trying to educate themselves, they found most of the material was provided from the outside worldview. How she wondered can we make the Elders be seen as professors? It’s a different way of thinking, and that difference needs to be passed on. From the region where we are from we did not go into wars and did not exclude other people. She described how the politicians are now talking about the Northwest Passage and about claiming this passage. How she wondered aloud can one get the international world to understand our notion of sovereignty? This is my territory, you are welcome to stay here but you have to follow our customs and our laws. Our tradition is in sharing. It has to be done in a respectful way.

Aaju concluded by saying that she and the others are trying to have BOTH Indigenous and western knowledge and systems, and want they to do it wisely. They want economically, socially, and culturally strong regions. They are doing this for our young people, for our youth. Lucien ….(Inuk Elder in residence for Akitsiraq) was integral to the success of the Akitsiraq program – students were so hungry for his knowledge; Lucien spoke about how voracious the appetite was to learn (in the past) – “How do we reawaken this hunger to learn?” he asked.

Tina Pars

Key Concepts:

1. The originator of the idea was the Prime Minister

2. Began small with 11 students, built over 15 years to 584 students

3. The University reaches for high international standards in our research and education programs, and subscribes to the Bologna principles

4. The university provides research-based education, with a view to communicate and exchange knowledge, collaborate with local society, and to contribute to the national, regional, and international stages

5. Recruitment of faculty is a challenge, as it is very difficult to attract skilled people to Greenland

6. Being too close to the government brings difficulties

Tina Pars is president of the University of Greenland. By chance she was in Canada and graciously agreed to address the group. Tina began by noting that the local name for the University of Greenland: Ilisimatusarfik means “A place where you gain knowledge”.

Tina began with an historical sketch of the origins of the university noting that the first ideas about the University of Greenland came from Jonathan Motzfeld, who was prime minister in the early 80’s, shortly after Greenland got home rule. The goal first was to bring home the Eskimology Studies at Copenhagen University; to have the responsibility for this study in Greenland and to establish a social science research environment in Greenland. The overall aims were to support Greenlandic identity, to “bring home” the Eskimology study from Copenhagen to Greenland, to establish a social science research environment, to support building Greenlandic identity and the development of Greenlandic language, and to serve as a node for study and education of Greenlandic language. The culture bearing programs were prioritized before law, business and other fields indicating the importance of that aspect to the Greenland people.

In the early beginning in 1984 we had 11 students at the Inuit Institute. By 1991 it was up to 60 students, and today we have 584 students on Illimarfik (the main campus).

Today we reach for high international standards in our research and education programs, and subscribe to the Bologna principles (See Appendix 1). At first, there were two undergraduate programs. Then, after a fusion with other institutes we had a teacher education, journalism, social worker and nursing school. From a perspective of progress, the nursing school is doing very well, but others are still developing.

Tina is the appointed rector and she has an appointed pro-rector and a board of governors. The foundation of the university is research. The university provides research-based education, with a view to communicate and exchange knowledge, collaborate with local society, and to contribute to the national, regional, and international stages. There is a movement all over Europe that calls for universities to open up to the society around it. This is also important for us. The committees of the university are the academic board, the board of Institute, and the quality and innovation board.

The Board of Governors has 6 externally appointed members, including 1 international; 5 internally elected (including 2 student reps). The Academic board is mandated to provide advice to Rector (President). Each Institute has a Board as well (learning process, institute of nursing and health research, and 6 others under one institute)

There are four Bachelor degree programs and one Masters program The university also offers BA and MA level in theology, social sciences, language, literature and media and culture and social history. Currently there are 120 full time staff, including 14 research faculty members, 40 teachers without research, 36 at Inerisaavik which is a pedagogical institute working on curriculum development for public schools, 32 technical and administrative staff, and up to 40 guest instructors.

Some diploma programs request tuition fees, otherwise all education is free. On an annual basis 800-900 students are leaving school, from this number 200 are graduating from high school, 56% of these graduates enroll at Ilisimatusarfik (the university). The university has on average 50 BA graduates and 3-4 MA graduates every year. From these an average of 40 graduate as teachers, 10 as nurses, 1 -2 in the social science, 1 -3 in language and media, less than 1 per year in cultural and history studies.

The universities direct and indirect influence on society includes establishing identity, nation building, and language development. Students get an analytical approach to language; students usually speak Greenlandic fluently. With regards to reporting and communicating generally there is clearly room for development. But as result of the university, we now have more educated Greenlanders. The Board is working with vision strategy. The university has established a definition of its values in regards to human rights, students in centre, and many more. Challenges remain in education quality, student environment, etc. In addition, the recruitment of faculty is a challenge, as it is very difficult to attract skilled people to Greenland.

The expectations that are directed at the university do not match reality in terms of economic possibilities and the university is very vulnerable to budget cuts. Tina remarked that being in charge of a small university is a challenge and how to provide growth when money and staff is small taught her to have more patience.

Tina emphasized that being too close to the government brings difficulties. Depending on money from government, having a department inside very close to the government, one cannot criticize it because it’s part of the university. What is growing is the internationalization of the university with regards to student exchanges, collaboration with society and business, student enrollment, and family support for children and youth to get educated. The political goal addressed today is to raise the current level of only 40-50% of Greenlandic population having an education. The political system wants this to increase. The University of Greenland is very much tied to the project of home-rule. Greenland has self-governance, so a bigger part of the population should take part in this task. The next years will focus on longer education programs such as teacher training, police education, and university studies. The university wants to build more dormitories because housing is a big issue in Greenland. Study guidance should be better, so that drop-out rates can be minimized and more students make the right choice in education.

Discussion and Questions

Joanne Barnaby

I’ve been dreaming this dream for most of my life. And I am really excited about coming together with people who share the passion for creating something that is not only needed but also something that should be highly desired by others, by the people in the north, throughout Canada, and in the world. I see the ways of thinking, the knowledge, the cultures, the values that we have in the north as being a real source of strength, of answers to a lot of problems, to a lot of modern challenges, and I see that we’re missing out on the opportunity to share those insights effectively with the rest of the world. And I am concerned that by ignoring those opportunities we’re hurting ourselves and depriving ourselves and the world from really making changes that would insure our survival long into the future as human beings and as life on this planet.

And so, I see the key element of what it is that we have to offer the world as a distinct way of being is our way of relating to creation, to each other, to other life on earth. And so that understanding, perceiving, relating is something that western thinkers and western science, at least in its current states of evolution, are way behind. There is a level of sophistication in those traditional understandings that is not even understood, let alone practiced in other modern systems. It really concerns me that we’re missing out on that. And we are losing that internally as well, as we change our relationship with the natural environment. We miss out. And we lose the opportunity to build that personal relationship with the universe that is rich with insights. And so I see the need to, and this where my lifelong work is, develop an appreciation of that.

There is the need for us as Aboriginal people to approach an understanding of ancient knowledge that can ensure its integrity through things like research, in ways that don’t change the outcome, that honors the spiritual nature, that also can be understood by other cultures and other ways of knowing. It’s our responsibility to take that challenge on and to ensure that our distinct way of knowing is in fact living, that it continues to evolve, it’s not a knowledge system of the past, it continues to grow and to evolve. I have this little fantasy that in my old age I will be working on designing a curriculum, on designing ways to draw this out which is in all of us. It’s actually in our genes, every human beings genes, not just Aboriginal People. We just have a more recent awareness of it, that awareness has been lost in other cultures. I want you to help me do that!

Mindy

Has Akitsiraq resulted in any “system change” as yet? Or are you forced to fit into the system?

Sandra

I feel far more confident, and realistic, in creating Makkik (Nunavut uranium mining watchdog). We are not to exclude one from the other, we want both, we want to do it wisely. I look forward to hearing the presentations on how we will be able to accomplish that. When I came here it was the wish for the future to become an economically and socially strong region when you have unemployment and all these things happening around you. In including our people in everything that we do is our key asset. To empower our young people, so they don’t have to go down south. The reason I could finish my education was because it was in our territory and in our language. When we had the Elders teach us traditional Inuit law, we had so many questions, he had so much knowledge, we were hungry for this knowledge. I wish to quote from him:

…(quote in Inuktitut meaning:) as children they are taught skills with the aspiration of having a bright future, they wanted to learn more and more and when they became the leaders themselves they would be equipped with the skills to provide for their family in the region and to ensure that nature is taken care of. We have to take that back, the will to learn in the language and in the setting, to respect who we are and where we are coming from. You can’t put a dollar value on this, it is so valuable

Question

Now with the knowledge you’ve learned from the Elders, how did it enable you to change the system?

Sandra

Changing the system cannot happen overnight, not with 11 graduates. I think it’s all the little things you do, I am involved in civil society fighting over resources extraction in our region, trying to practice a different approach, creating a philosophy that changes things ever so slightly, that changes the dynamic in the work place.

Anne Supplemental answer

You could see the difference of their approach.

Ellen

As you grow in your practice, you will also be involved in research, research is increasing knowledge, that is the function of university. You can look forward to new information in whatever form it is.

Carla

For us knowledge is different. It’s very interesting to see who passes on knowledge, what kind of knowledge. Talking about university in Nunavut, the kind of research that would be done, you can’t even put a dollar value on this, it is so valuable

Alan

It is important to keep an arm’s length distance between institution and government. Government will try and influence through funding and grants, but should not be involved directly in governance or programming

Mary Jane

There were common themes in all presentations: one of the common things was identity, another key is language, traditional laws and governance, different thought process from an Aboriginal perspective, pursuing the idea and bringing it home to traditional territory. It is the very basis of exercising sovereignty.

Appreciative Inquiry

Core Values, Common Themes, Guiding Principles, Best Practices

Creating a Vision

Part #1 – Setting the basics for a Vision

Introduction

In this part of the program participants were asked to hold in their minds the information and impressions from the round table speakers and to recall the feelings and impact of some of the words and stories that arose during the appreciative inquiry process. In this context, the participants were asked to dream about a university and to imagine what it might be like. The dreaming was to become the backdrop for a series of five questions that would help to draw out the essence of a university that is relevant and appropriate for the North. The original intention was to split up in groups to respond to the questions.

A Dialogue to Clarify the Indigenous Position

As the five questions were set up, one of the participants indicated a degree of apprehension describing her reactions as a reservation resulting from the exploitation she had previously experienced that was preventing her from opening up completely.

“Where is the information going?” she asked. “I fear that someone might take the information and run away with the project.”

Another participant elaborated to say that the group was here because it is their responsibility, but that it is a racial trust issue because of the history of exploitation. She explained that she also had this reservation but did not want to cause animosity.

Another participant remarked: “This opened up a can of worms and I am feeling uneasy.”

Alan, the non-aboriginal facilitator responded to say that the result of this project will be a vision statement that this group will present to another group of people who ultimately can champion the concept. It will be important for this working group to own the results and to move forward with the results to create a university of the North. He went on to explain that as someone with a great deal of university experience it was his role to assist everyone to frame their ideas (not his) into a package that universities can understand.

To allay some of these fears, James (executive director at the Gordon Foundation) explained the end product and its distribution carefully. The aim is to produce a very nice looking report that is distributed publicly as well as strategically. That we can commit to do. Feeding into that we would love to have some quotes, from the survey, from participants, and from potential champions. Before we send out the report we will send out to everyone to review it. But in terms of controlling of what goes on beyond that, all we can do is support it. The territorial governments may not necessarily be happy with us for doing that, since they want to control it, but as we are paying for this and as our emphasis is on the grassroots, government control of this dialogue process is out of the question. This report can provide a different point of view. We can bring people together, and can help advocate in-kind beyond, where requested, but that’s the end of the road for Gordon foundation on this process, officially.

The fact that this issue arose was exceptionally instructive and the ensuing discussion became an important part of ensuring that the aboriginal participants could ultimately feel comfortable enough to voice their opinions and have their voices heard in a way that appreciated the aboriginal voices and opinions. In addition the format of the report and process of delivering the final vision ensured that the vision and the conceptual basis of the university was defined and presented by this group ensuring that the ownership of the concept was clear. But the discussion underscored the historical exploitation giving rise to difficulty of aboriginal people relating easily to western styles of thinking and in this case to the western concept of a university.

The final solution allowing the project to move forward was working on each of the questions with the group as a whole so everyone participated in all aspects and nothing was done separately. Joanne summed it up as follows: “I think that is a great idea, it’s a way of building consensus. In terms of where this goes from here, my reason for getting involved in this project is for those reason, the three northern governments have all included the establishment of a northern university in their strategy. To me that doesn’t mean anything, they have talked about this for a long time, and the way they do this has little to do with my vision. So in order to contribute, I want to ensure that my voice is heard, to ensure that voices of people who have visions are heard, voices that are not mainstream. I have a sense of responsibility to share my vision with other to help create it. If I don’t make a contribution it’s going to be so much worse.”

Other fundamental concepts that were brought forward in the discussion included remarks such as:

“This is exactly the dialogue we need. It is very important for me to hear the voices of indigenous people of what they dream. We wanted to hear from the real people. We’re coming here with our own views of what it means to us, what we want a learning facility to be.”

“I may represent the ICHR but in any dialogue like this I am also representing my people and as a community person I represent the Gwich’in wherever I am. I would like to resolve it with the help of others.”

“This is what I understood for the dialogue, this is what would come out, people ask questions, think out loud and people aren’t going to cut you down. We always have to speak for the last generation, our parents were never asked: what do you think? My parents were very reluctant to say what they really think. That is part of the dialogue to learn to say what we really think.”

“When I thought about this university – I know that aboriginal languages speak at a different level, a depth with how people talk. There is a story about a sister and brother and it had all these layers of explanations, of rules, of taboos, and I thought wouldn’t that be wonderful to teach that in university? It goes back to such a long time. It is the animals’ land that we are on here. That’s my vision for a university; to teach at that depth and then bring it to the outside people.”

The Process

Five questions were posted on the wall for everyone to see. Each participant was handed three cards with the expectation that they would fill out three answers for each question. As each question was completed, the cards were collected and placed together on a single board in front of everyone. Then as a group the cards were rearranged in to categories based on the answers that were received. This is a highly interactive task with members of the group calling out instructions or approaching the board to physically change the card positions. Still in group mode, the cards are then assessed for similarity and set into groups under each category (defined by a card). Once the question has a set of cards in categories and the cards are grouped according to similarity under each category, the group is asked to make sure the cards reflect the group’s opinions and priorities. In the end the result is a response to the question in the form of categories with explanatory words or concepts in each category. The cards that people donated are intended to spark debate and represent entire concepts, so a list of the cards alone is not sufficient to provide the depth of meaning suggested.

Thus, each question is followed by a summary of the essence of the discussion and cards. The actual cards and categories are listed to provide a sense of the diversity of ideas discussed. In some cases, individual cards were debated as to their relevance, but in most cases all cards were included even if they essentially duplicated ideas.

Question #1

If you were in charge what three major areas of university activities would you emphasize?

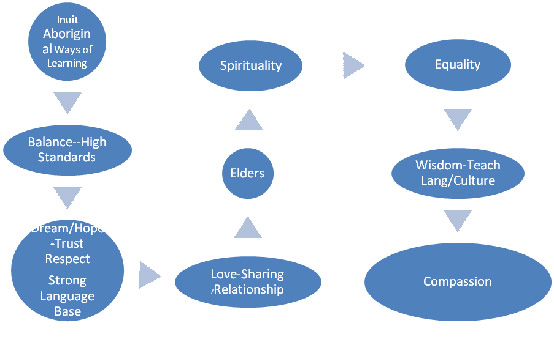

The Main Points

The major thrust of all the priorities was to emphasize the aboriginal context including the language, culture, spirituality, and ways of learning and teaching as well as the traditional knowledge of the Elders. The context for all such learning is the powerful relationship to the land. Indeed in all of the answers a recurring theme was teaching on the land where the reality of the world is immediate and ever-present, rooted in the sense that people are a part of nature, not the owners of it. In all of this teaching, the Elders are the key ingredient. Without them, it is difficult to imagine success in this context.

The second priority was to ensure a positive and balanced approach so that a healthy perspective is maintained. This balance includes perspectives on life, spirituality, trust and respect, and equality of all. This sounds easy, but the historical perspective, post-western domination of the aboriginal peoples, is very different and that imbalance continues to the present day. The earlier discussion to clarify the aboriginal position for this discussion was immediate witness to this problem.

The third most important was to engender hopes and dreams through love and compassion with the Elder’s ability to impart their wisdom and humility to engender a desire to share and contribute.

Many other ideas were added to the mix including specific suggestions for curriculum topics such as the history of the North. This is always an interesting subject because the current history of the North does not include much of the indigenous history, while in fact, that comprises almost all of the actual history of the North and could only really be taught by Elders.

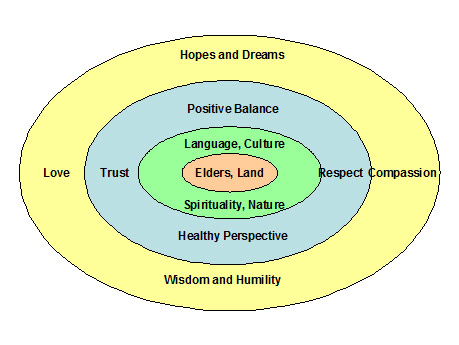

In summary, however the sense of the group was to have the land and the Elders as the base of everything teaching about nature, culture, and spirituality in the languages of the North all in the context of trust and respect to achieve appositive balance and healthy perspectives on life. By doing this the university would achieve the hopes and dreams of the members engendering love, compassion, wisdom, and humility.

The Cards Submitted

Land + culture: indigenous centered, teach history of north and its people, promote histories, stories, legend of the people of the north, cultural validation, world view and culture and language,

Perspective and balance: perspective, inclusivity, acceptance, inclusiveness, acceptance of differences, esp. methods of teaching,

Inuit way of learning: By Inuit, By Indigenous, curiosity

Balance: self-determined, ethics and the land, respect for place

Spirituality: spiritual, Dream, hope, Compassion, Love

Elders: taught in indigenous languages, respect for diverse knowledge grounded in place and languages

Trust respect: respect + sharing, credibility and trustworthiness esp. holders of knowledge, respecting culture and language respectful, respect and sharing, equality

Wisdom: desire to learn, achieving competence with humility, challenge: personal, intellectual, inquiry

Teach language and culture: Sharing, relationship: language, freedom of wide expression, diverse, Strong language base

Question #2.

Imagine the university has been established for 25 years. Describe how the North would have changed? What issues might have been resolved? What new knowledge would be developed? Would cultural conflict be heightened or resolved? Would there be increased recognition of differences or would the differences simply be less important?

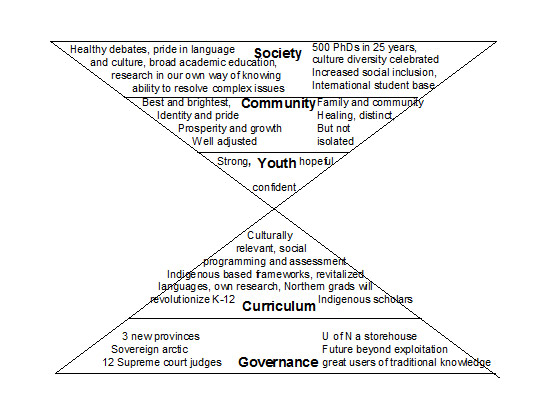

The Main Points

It became clear that the university and the community would in fact be intimately connected after 25 years. The development of the university and certain aspects of its character was an important foundation for predicting what impact it might have on society. The group was not asked to define the university but instead to imagine the university as a context for what might happen to society. Interestingly, the cards submitted did in fact define the university as well as its impact suggesting the two are so intimately linked it is not possible to have one without the other.

The foundation of the university – its governance – includes the idea of a surrounding context of three new provinces and graduates comprising the Board, speaking in indigenous languages and conversant with traditional knowledge in a setting free from exploitation.

Even the curriculum was indicated with culturally relevant social programming and assessments in an indigenous-based frame of reference. The notion of developing the K-12 schooling as a prerequisite to building a university-capable population is an important underpinning. In addition the idea of northern-based research embodying indigenous languages, using graduates from the university highlights the essential concept of inclusive independence.

Supported by this definition of the university, the impacts were aligned in different levels from the broadest aspects of society to the community level and finally focused directly on the young people. In a sharply defined statement the young people are seen as strong, confident, and hopeful – an especially powerful statement considering many of the issues facing young aboriginal people today. Communities were imagined as healthy, proud of their achievements, prosperous well-adjusted, and distinct but not isolated from society at large instead growing in their abilities to understand themselves and other people.

The university was seen to have influenced northern society in the broadest possible way. The university was seen to engender healthy debates, pride in language and culture, research in the northerner’s own way of knowing that would result in the ability to resolve large and complex problems on their own. In fact, one suggested that in 25 years they should be able to graduate 500 PhDs. Importantly the university was imagined to enhance cultural diversity and to increase social inclusion, and even develop a broad international student base.

Society: healthy debates, people committed to relationship with the land, people proud of their language and culture, broad education more than trades-for-$ will be valued, more respect across and in Yukon, NT, Nunavut, and South, academically educated people, North is part of Canada and contributes to research from our own way of knowing, ability to resolve complex northern issues by educated northerners, 500 PhD’s in 25 years, cultural diversity will be celebrated, increased social inclusion, Inuit in all the professions that we currently hire from elsewhere, Students from around the world applying

Community: stronger individuals, best and brightest close to home, healthier economy, , well adjusted people, more respect, identity and pride, family and community healing, better understanding among people, identity and pride, northern cultures prosper and grow, remaining distinct but not isolated, extensive language users

Youth: Young people educated academically and traditionally, academics, strong and confident youth, our children carry our knowledge to the world, smart confident youth, youth will have hope, suicide disappears

Curriculum: culturally relevant social programming and assessment, frameworks that are indigenous based and centered, revitalization of languages, north conducting own research, increased indigenous scholars and teachers, university graduates will have revolutionized the K-12 curriculum to be culture based, establishment of community-based university

Governance: great users of traditional knowledge, we remain distinct but not isolated, IQ TK respected, 12 Supreme Court judges, future beyond exploitation, regional universities established, University of the North a store house, 3 new provinces, sovereign Arctic with international status, system of governance in place

Questions #3 and #4

(These two questions ended up being answered together.)

If you were hiring faculty or setting standards for students, what kinds of requirements would you look for? How would you judge the standards for Elders, for traditional knowledge, for students that would be applying? If you would describe the University of the North to a person interested in applying as student or as faculty, what would you talk about?

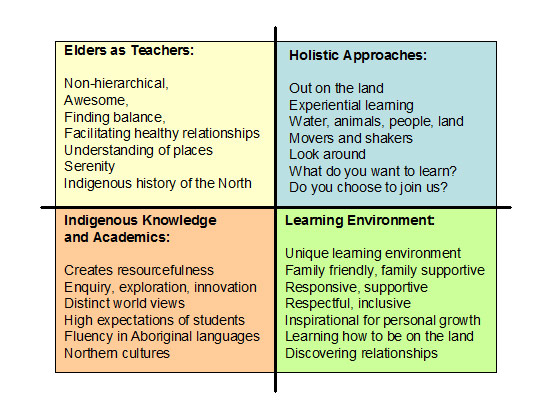

The Main Points

In this discussion, there was some considerable hesitation about the suitability of terms such as “faculty” and “students” in a university with such a strong indigenous focus, and most especially as applied to Elders being thought of as faculty. The breakdown of thinking seemed to deal with the “teaching and teachers as one two-part element and “learning and learning environment” as a second two-part element.

The Elders are seen as awesome non-heirarchical teachers who encourage their students to find balance in life by understanding the land and the serenity it can bring. The Elders are uniquely capable of recounting the history of the north in a way that no non-aboriginal could deliver. The result of this interaction with the Elders promotes within the student a new resourcefulness, a desire to explore and innovate as well as enhancing a distinct world view. Elders will teach in aboriginal languages so developing a fluency in local languages is imperative. This illustrates the high expectations the group saw for the students.

Equivalent to the Elders in a learning context is the idea of being out on the land, involved in experiential learning about water, the animals, the plants, the spirit world – a holistic approach to learning. The result anticipated is that the students will become the next movers and shakers, but to do that they must want to join the university and must choose to do so on their own, not because they are told to do so. To make all this work, the university will need to be family friendly and supportive. Within this unique learning environment the students will learn respect and inclusiveness, how to be on the land and how to discover the relationships around themselves, a completely inspirational setting for personal growth.

The Cards Submitted

Elders: Non-hierarchical, facilitating healthy relationships and understanding of places. Awesome, finding balance, serenity

Redefining the learning environment: tell us what you want to learn, look around, can you contribute?, can you know us by your students?, do you choose to join us?

Focus on Indigenous knowledge and academics: knowing what and how TK is used, Indigenous Assemblies, creates resourcefulness, serves country food, programs incorporate traditional knowledge and a history of North, incredibly unique learning environment, inspirational and supportive place of learning for personal and societal growth, a place of inquiry, exploration and innovation that draws on distinct world views, high expectations of students, , exchange of knowledge, taught in aboriginal languages, learning aboriginal language, no need to speak English, fluency in languages, U of N teaches language and culture

Family friendly: supports students and staff like a family, community of the U of the North, responsive, respectful, inclusive

Holistic approaches: out on the land, do you want to be part of the next group of movers and shakers? Land based experiences, N of 60 generally, experiential learning, leader in environmental studies, knows how to be on the land, lifetime experience you will never regret, on the land classroom, of the land, water, animals, people, learning through experiences on the land

Question #5

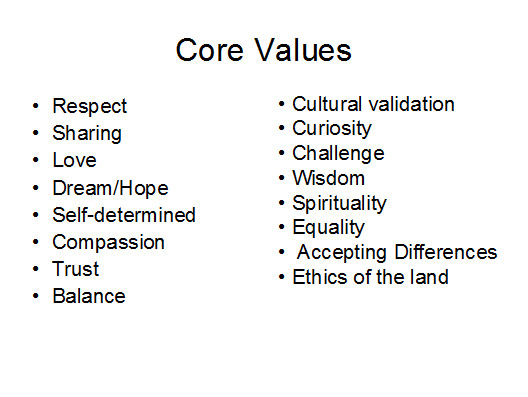

What three core values would you feel should be at the foundation of the University of the North?

The Main Points

“Core values” is a common phrase used in western business and in universities. Although familiar to many of the indigenous people in the group, there was some hesitancy in applying the words in an aboriginal context. The result was that the values expressed are both similar and interestingly different from core values often stated in western universities and most certainly different from many western business corporate policy statements. There seemed to be two basic types of values listed. The first list comprises values normally expected of decent human beings living in an enlightened civil society. Such values as respect, sharing, love, compassion, trust and so on. These were foundational to the indigenous cultures (and many other cultures as well).

The second set comprised values that will be acquired while in the care and tutelage of the Elders and in an on-the-land setting. They also reflect the historical reality of the indigenous peoples: cultural validation, challenge, spirituality, accepting differences, and the ethics of the land.

Taken together these values represent a mix that would serve humanity as whole very well. As a goal for the university, the aim is set very high indeed.

In considering the core values, the group also created a diagram of how these core values might come together in a matrix of relationships. Elders are central and surrounded at equal distances in this thought experiment with the other aspects of the value system.

The Cards Submitted

Language, indigenous knowledge and ways of knowing, land, respect and sharing, culture, ethics on the land, inclusiveness, Inuit ways of teaching and learning, challenge, Elders, love and wisdom, spirituality, teach history and stories of the north elder, curiosity, land, culture, respect, self-determined, indigenous languages, acceptance of differences esp. methods of instruction, cultural validation, high standards, compassion, trust, balance, dream hope, acceptance, love, by Inuit, by Indigenous, respect for knowledge grounded in places and language, promote history, story of the north, equality.

Summary of the Results of the Questions

This completed the first day of the work shop. The day began with a discussion of the context for a proposed University of the North by people who know and live in the North and who had thought about the need for a university for a long time. Next the group shared learning experiences in the North on a very personal level. Insights gained in this section flowed over to the answers supplied during the period when we dealt with specific questions using the card technique.

The results describe a unique university concept, specific to the North and responsive to the historical realities as well as the current issues for indigenous people in the North. The basics of the university were defined: the core values, the main areas of academic enterprise including research, the types of students and faculty that would be engaged, including the learning and teaching styles, and finally even the goals stated as impacts on society for a 25 year horizon. The essential differences however were in the aspects that reflected the unique culture of the North having a mix of western and indigenous cultures. The need to rebuild the many indigenous cultures and languages came through very clearly as did the root cause for the erosion of those cultures and languages. Elders and on-the-land experiential teaching methods reflect the imperative to apply indigenous teaching methods and to learn traditional knowledge. Because of the historical exploitation of the indigenous societies and the sometimes exploitative research of southern universities wherein the research is carried out on or with aboriginal people but no results are sent back or shared, the proposed values and curriculum contain approaches designed to repair the damage and to build to a new and healthy future full of hope.

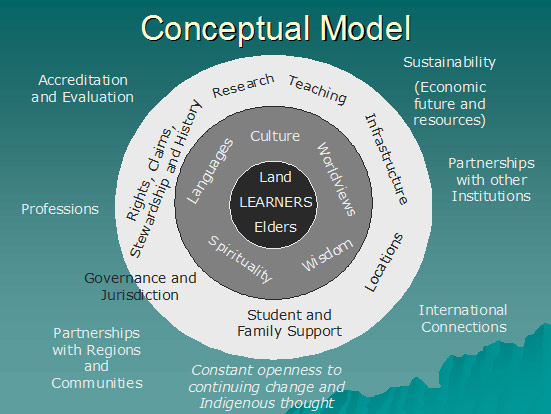

The following day the group was presented with a conceptual diagrammatic summary of the concept of the university building on the questions from the previous day and asked to edit and add to the diagram so that it properly reflected their deliberations. The conceptual model uses inclusive circles that acknowledges expanding layers of influences.

The conceptual model begins in the innermost circle centered on the learners, conceived as rooted in the land, and mentored by Elders. This theme of on-the-land learning with Elders was probably the single most important and frequent aspect of the discussion about the university.

The next circle or ring provides the context within which the learners will interact with the land and the Elders. Specifically, there is envisioned an indigenous culture combined with other cultures and world views that come together in the spirituality of being on-the-land with Elders who can impart wisdom both from ages past and also in a modern context. All of this can take place in indigenous languages thereby ensuring a correct interpretation of the stories of the Elders.

The next ring is the more familiar aspects of a university: where it might be located, what it would look like, the actual teaching curriculum and mix of faculty, and subjects of special interest such as the backdrop of the history of the North such as the current rights, claims, and stewardship. Research – the search for new knowledge and understanding of the universe as well as the world around us in subjects ranging from science and philosophy to culture and spirituality – is also in this ring. Linking this ring to the final outermost ring is the connection between the university and the governance of the institution both internally by the Board of Regents and the government jurisdiction by the territories and federal government at the political level.

The final outer “area” is the larger world in which the university finds itself. Here is where the university is a member of a community of universities. Within this community the university must strive to reach the academic standards that will allow it to award undergraduate and graduate degrees. Accreditation and evaluation are important facets of reaching for academic excellence. The university strives to bring new members to society trained as professionals at the very highest level. These graduates bring new knowledge on which new technologies can be based to be shared with the world. This search for new knowledge develops international connections of many types ranging from professional to commercial. One of the most critical aspects of any university is to develop a sustainable base for economic and other resources. To do this the university will need to develop partnerships with other similar institutions, with institutions that have complementary skill sets and interests, as well as with local regions and communities. Outreach, giving back, sharing, inclusion are all aspects of a university that will be most important in the North. Finally in the tradition of indigenous knowledge as well as in western knowledge it is important for the university to be constantly open to change in circumstance and thought. Given the realities of global warming, there will be many challenges that a university in the North will be uniquely equipped to handle.

Purpose:

From all of these discussions and considerations as well as the individual thinking of the members of the group, a “purpose” or “mission”statement was drafted reflecting the conceptual model that was developed. The mission statement was entitled “Dene K’ekaedenia – Awakening the Spirit”:

Dene K’ekaedenia

Awakening the Spirit

The University of the North will awaken the spirit; learning through wisdom.

The University of the North builds on the traditional “way of thinking” enhancing the ability of the student/learner to be very educated on how to thrive and flourish by learning from the best.

Centered on Elders and other mentors, the land, and learners, the University of the North will ensure that our graduates and scholars will become proud standards of our land, communities, and way of being.

Creating the Vision

Part #2: Composing and Writing the Vision

On Becoming a University

Introduction

There are no universal systems for accreditation of universities. Europe adopted the Bologna principles in 1999 and these have become the principles on which universities in Europe operate. In most countries the state (either federal or local) provides a charter (similar to incorporating) for universities and colleges to operate and to grant diplomas or degrees. In all countries the graduate programs and professional schools such as medicine, engineering, sciences, and so on have rigorous discipline-related accreditation procedures.

Canada has no formal system of institutional accreditation. However the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada has criteria for membership that serve well for this purpose. For a great deal more specific information on the hurdles, criteria, and thresholds to becoming a university be sure to read and study Appendix 3. In Canada any institution that has membership in AUCC in conjunction with a provincial or territorial charter can be consider an accredited institution. Only colleges that offer degree-level courses and programs are considered eligible for membership in the AUCC. Thus, in general “community colleges” that specialize in technical or trade-related courses are not eligible for membership.

Where Does the University of North Stand at this Time?

As a result of the meetings held at Trappers Lodge and at the Explorer Hotel in Yellowknife, the proposed University of the North has several of the requirements in conceptual form such as a Vision and Mission statement as well as at least loosely defined academic goals.

It has a conceptual model that if implemented would satisfy many of the requirements for academic staff, although some form of accreditation for Elders will still be needed for them to qualify as having academic authority. Conceptually the model can be considered to include a president and senior officers as well as an “elected” academic senate although the notion of a non-hierarchical institution will need some explanation so the association can understand how the model can encompass the same roles. The model includes specifically a board of governors which although not explicit in the current documents implies financial and fiduciary control, is representative from the university’s external stakeholders and uses the institution’s resources to advance the institutions mission and goals. The model is specific to its intention to teach and disseminate knowledge, to carry out research, scholarship and the advancement of knowledge, and to service to the community.

The requirement to have as its core teaching mission to provide education at the university standard will need to demonstrated and proven in practice, especially as the traditional knowledge of indigenous peoples has been a subject of research, not normally material for course content.

Accreditation of Elders at the PhD level can be managed by a clause “…allowing for relevant professional experience where appropriate”. Each Elder would individually be acknowledged presumably through some process yet to be developed.

The proposed university of course has no experience record (unless Dechinta and Akitsiraq and similar programs agree to be folded into the proposed university). These programs also demonstrate a capability to develop undergraduate degree programs that could be considered equivalent to standard liberal arts or science and first degrees in the professions such as law, medicine, engineering, etc. In general however, even in the conceptual model there is nowhere near enough detail to satisfy the extensive criteria and indicators that define an academic program within a university.

The proposed atmosphere of the University of the North will be even more inclusive and encouraging than the current requirements.

There are a number of conditions that make it especially difficult to be a free-standing institution and acceptable for membership: it would need to have demonstrated three consecutive years of operating at the university level with 500 full time equivalent students enrolled in university degree programs. Therefore, the most direct route to becoming a university would be to begin as a constituent part of some other partner university or universities, or conversely allow the current colleges to continue to evolve to become universities, but work to ensure that the principles defined in the work of this group are included in the evolving universities.

Regardless of what route to university status is chosen, it is very important to recognize that at this stage, the proposed University of the North has none of the formal requirements that would allow it entrance as a member of AUCC.

What are Acceptable Options for a University of the North?

The working group was challenged to make certain that a university is what was wanted. The answer was a resounding yes, it must be a university. The implications of this “yes” statement are profound. No group or institution has the right to become a university in Canada without following a set of rules and without meeting a set of criteria as well as being able to sustain itself financially and academically with a full time enrollment of at least 500 students. In addition the only way it can begin is by gaining charter status from a province or territory and being voted acceptable to the Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada.

There are good reasons for these exceptionally high standards. Currently 95 institutions meet these standards in Canada and all of the courses taught, all of the degrees granted and all of the successfully graduated students can be relied on to have reached similar standards of excellence. Thus, if a student wants or needs to move from one institution to another, either within a degree program or to advance to a higher degree the receiving institution is able to receive that student on an equivalent footing to its own students. Internationally, as well as across Canada, the disciplines associated with medicine, engineering, and other professions requiring high standards set those standards so that even in international transfers the degrees and course are approximately equivalent, although usually require some measure of additional training to meet local standards.

In any model, following the trail to a university that has at its core the concept of indigenous knowledge and indigenous teachers will take time, especially as these are not within the current regime of the accrediting organizations. The key academic and accreditation issues will be based on the unfamiliar territory of traditional knowledge as a core course with content drawn from traditional knowledge. Unfamiliar subject material and unfamiliar techniques bearing heavily on experiential learning will also be difficult for a western academic to know how to test for successful completion. In addition, the Elders who are in many cases holders of great storehouses of knowledge and abilities to apply that knowledge to modern-day problems and issues nonetheless are in a system which today has no “observable” standards to western academics.

In a broader context, it has been found that bringing western approaches and traditional approaches together can be difficult especially if the short-term goals are not the same. However, success has been achieved by interweaving the two approaches, rather than attempting to coalesce them together under a single approach. Similar successes will need to be demonstrated, probably many times before the relatively conservative university systems will understand and accept them.

Hypothetical Models for the University of the North

The conceptual model described in this report implies a number of potential physical models. The hypothetical models described here begin with the conceptual model described in this report and speculate on how this concept might be applied in a physical setting and still meet the political and academic requirements of the reality of being a university.

The basic physical/political variables are:

1) Free standing or affiliated

2) Campus-based or distributed

3) Broad-based or specialized curriculum

Each of these variables is a continuum, it is not an either/or situation. For example let us consider the first variable. One end of the continuum is a free standing institution. The other is a collective of affiliations (such as the Huntsman Marine Lab or the Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre). In between there are potentials to grow from a department in a university or to be partnered with several universities so that a number of specialty programs can be offered in addition to the required range to qualify as a university.

The second variable is also a continuous variable in which the classical image of a single campus with magnificent and imposing buildings can be compared to a university that is largely taught over the Internet and has almost no physical infrastructure, or as might be imagined in this context a series of campsites and regions to explore and experience the teaching methods of Elders.

The last variable is about the breadth of subjects to be dealt with. At the undergraduate level, it is required that a broad base of liberal arts and sciences be taught as well as a reasonable offering of programs designed as entry level degrees leading to professions that ultimately require higher levels of learning and advanced graduate degrees. Specializing in one or more programs leading to advanced degrees however is where this variable can be expanded or contracted. For example if it were part of the strategy of the University of the North to specialize, it might have advanced degrees in aspects of traditional medicine/healing/philosophy/spirituality. Or it might decide to be the world expert in environmental issues dealing with global climate change in northern environments. Another possibility would be to have interwoven programs using both western and indigenous approaches together to solve issues typical of the North.

On-The-Land University of the North: Expanding the Dechinta and Akitsiraq Models

Without slavishly copying the Dechinta model, but instead using it as an inspiration for a university, let us imagine what the university might be like. In this hypothetical model, there might be a short list of affiliations with external universities designed to allow a broad-based series of the equivalent of liberal arts and sciences, but with a decidedly northern flavour, highly spiced with indigenous knowledge and teaching methods as well as more typically western subjects. Imagine the university as having a range of locations. Perhaps a modest central building in a location can serve as home base close enough to a populated centre that it could house technical requirements for computers linked to the Internet via satellite so that distant battery-powered laptop or netbook or even “pad” style computers can be used almost anywhere. In addition the building might be surrounded by cabin style residences for temporary accommodation or family-friendly residences for students who are on-the-land. Perhaps a network of semi-permanent campsites (in the tradition of hunt camps or fish camps) situated to enhance the topics being studied are scattered across the North. Imagine research outposts semi-permanently equipped to handle social, health, or environmental research. Both the campsites and outposts would be located close to existing towns or villages so that the local people can be included and informed about the work being done.

The University of the North in this configuration is physically a modest university building surrounded by a series of small buildings that can act as residences or even small study areas, but the main campuses are scattered campsites and research outposts. Now in our mind’s eye, let us superimpose the conceptual model over this physical model. How well does it fit? Land Elders and Learners are together at the conceptual (and in this case physical) core. It completely supports the next ring, and at least to some extent completely supports the third ring of research, teaching, family support, and handling specific northern needs. Even the relationships other institutions, communities and international connections is handled well.

Is it weak in any sector? Perhaps in the area of teaching entry-level professions, one would need to ensure a period of time in a more western-style setting in the central building. The example of the Akitsiraq success is useful in that a fully professional entry level degree can be handled in a northern setting using minimal resources. The two big issues are probably sustainability and accreditation.

To test this model further, on top of the physical model and on top of the conceptual model, let us now in our mind’s eye superimpose the requirements and criteria for entrance into the membership of the AUCC as well as the requirement to be chartered either directly (in this case by a Territory) or indirectly (via partnerships with one or more other universities). Taking experience from both Dechinta and Akitsiraq, a workable model would be to begin as a set of programs supported intellectually, academically, and financially by a number of universities all housed in a an organization managed as the equivalent of a university “centre” or “institute” to begin with.