Ecological systems are observed associations of species in specific environments or regions. Without insisting on a slavish copy of this concept to economic systems, it is important that the elements of an ecosystem and an econosystem remain at least parallel or the benefits of the predictive nature of ecosystem theory will be lost to the econosystem. To that end, let’s return to the species/lucrespecies parallel. A biological species is a population of individuals with similar characteristics that reproduce more like individuals. A lucrespecies is analogous in that it is a population of entrepreneurs with similar characteristics and that tend to create more entrepreneurial entities that are of similar characteristics. I previously chose the example of the biological species of human beings (Homo sapiens) as analogous to the lucrespecies of car manufacturers. In these two analogous species, the individuals are respectively people, like you, and corporations, like Honda and Toyota.

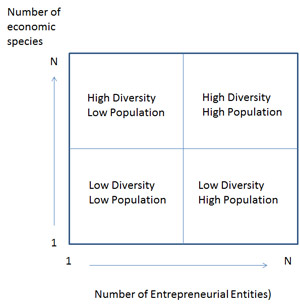

So to look for and distinguish different econosystems, like different ecosystems, one must look for assemblages of lucrespecies in specific socio-political environments or geographic regions. In a previous blog, I mentioned some terrestrial ecosystems. Without doing too much imagining, if I ask you to visualize a tropical savannah I am sure that in your mind you see rolling plains of grass and shrubs mixed with isolated low trees and herds of large herbivores. I also imagine you would not have much trouble telling me what is the top predator. This is a relatively simple ecosystem by comparison let’s say to a tropical rain forest. Can you as easily tell me what the major herbivores are in a tropical rain forest? Or what the top carnivores might be in a South American rain forest? This is a much more complex ecosystem with many more and much smaller species in general than a tropical savannah. A tropical desert is even less complicated, although probably less familiar.

Continue reading